- Home

- Richard Kurin

Madcap May

Madcap May Read online

© 2012 by Richard Kurin

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

Edited by Owen Andrews

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kurin, Richard, 1950-

Madcap May : mistress of myth, men, and hope / Richard Kurin.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58834-327-7

1. Yohe, May, 1869–1938. 2. Singers—United States—Biography. 3. Women singers—United States—Biography. 4. Actors—United States—Biography.

I. Title.

ML420.Y64K87 2012

973.91092—dc23

[B] 2012006210

Excerpts from Hope Diamond: The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem by Richard Kurin courtesy of HarperCollins and Smithsonian Books.

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen on this page. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

v3.1

For Allyn, who is so not May

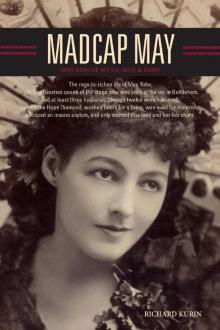

Sketch of May Yohe, 1895. (photo credit col2.1)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

CHAPTER ONE Bethlehem’s Daughter

CHAPTER TWO Footlights Goddess

CHAPTER THREE Nobly Courted

CHAPTER FOUR Hopeful

CHAPTER FIVE My Honey

CHAPTER SIX Aristocratic Artist

CHAPTER SEVEN Destitute Duchess

CHAPTER EIGHT New York’s Finest Lover

CHAPTER NINE Exotic Romance

CHAPTER TEN Betrayed, Again

CHAPTER ELEVEN Independent Woman

CHAPTER TWELVE War Bride

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Cursed

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Domestic Tranquility?

CHAPTER FIFETEEN Mother?

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Poor, Ill, and Un-American

Epilogue

May Yohe Timeline

Acknowledgments

Notes

Illustration Credits

PREFACE

MAY YOHE (1866–1938) was the drama queen of her time, a woman who lived an amazingly tumultuous life in the period spanning the Gay Nineties, the Roaring Twenties, and the Great Depression. With her outsized personality, roller-coaster career, and endlessly complicated love life, she was the Elizabeth Taylor, Lady Di, Britney Spears, and Tina Fey of her era, all rolled into one. Yet today, her truly fabulous story is unknown, her name, pronounced “yo-e” (rhymes with “snowy”), unrecognized.

May Yohe, a popular entertainer from humble American origins, married and then abandoned a wealthy English lord who owned the fabled Hope diamond—one of the most valuable objects in the world and now exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Nicknamed “Madcap May,” Yohe was a favorite of the tabloid press. She was a romantic who had numerous lovers and at least three husbands. The tabloids claimed she had twelve, including the playboy son of the mayor of New York. May separated from him, not once, but twice. Her next husband was a South African war hero and invalid whom she later shot.

May Yohe was a sweet-voiced, foul-mouthed showgirl who crossed paths with many famous people, including Ethel Barrymore, Boris Karloff, Oscar Hammerstein, Teddy Roosevelt, Consuelo Vanderbilt, and Edward, Prince of Wales. George Bernard Shaw, the Nobel laureate and playwright, praised her for her lively presence and performance and then rebuked her soon after for going stale. In later years she faced several maternity claims and a lawsuit, which she won. She was hospitalized in an insane asylum and escaped. She ran a rubber plantation in Singapore, a hotel in New Hampshire, and a chicken farm in Los Angeles. When all else failed, she washed floors in a Seattle shipyard and, during the Depression, sought a job as a government clerk. Shortly before her death, she fought successfully to regain her lost U.S. citizenship.

How was May Yohe able to charm her way to international fame, live an improbably complicated and adventurous life, and find the strength to persevere in light of the losses she suffered—in wealth, citizenship, love, and sanity?

This book, assembled from her writings and historical interviews, archival records, newspaper stories, scrapbooks, photographs, playbills, theatrical reviews, souvenirs, and silent film, tells her heretofore lost story.

That story is one of a particular kind of feminism. Yohe was pretty, but not beautiful. She had an alluring, almost innocent sexuality that she used ably, willingly, and often to attract admirers and lovers. Yet she had her greatest success on the stage playing young male roles. Her ability to radiate sensuality as both faux male and femme fatale set her apart.

So did her quick wit and verbal prowess. May could regale a dinner party with humorous anecdotes, but also curse like a Marine among men. Her one-line retorts were widely quoted. “What did she think about the bonds of matrimony?” asked a reporter. “Never paid me a dividend,” she snapped.

May shared with contemporary suffragettes and intellectuals a deep-seated faith in the natural, God-given ability of women to succeed. She was a so-called “new woman” of her time—an exemplar of femininity, applauded by some, scorned by others. But unlike pioneers of women’s rights such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, May was more concerned with her own success than the success of women in general. In a man’s world, she fought for a woman’s right—her own—to live freely. She conquered skeptical audiences to gain stardom and fought British nobility to gain legitimacy. Her public persona often appeared selfish, even narcissistic, yet time after time she defied expectations, doing charity work for London’s poor and Ireland’s farm workers, ministering to war wounded as a nurse, and defending chorus girls from moral attack. She repeatedly challenged authority figures who stood in her way or sought to do her wrong—the courts, the critics, the government, the British peerage. She also surmounted her ambivalence about the curse of the Hope diamond—a legend she herself helped invent.

May Yohe’s resolve to win her battles and continually pick herself up from divorce, deceit, fraud, poverty, and disenfranchisement stemmed from a strong, almost uncanny adherence to her own self-made, ever-changing image. May saw herself not as a victim, but rather as a protagonist who had the power to fight, fend off wrongs, and gain her just rewards.

Her strength of character was built upon her upbringing as a Moravian, a member of a religious sect that emphasized female spirituality, musical virtuosity, sexual frankness, and a worldwide ecumenical outlook. Though May was by no means religious, these values, in a secular (some would say profane) form, became part of her personality. What is more, May was literally born at the inn in Bethlehem. While this was not the Bethlehem of biblical repute, but a small, bustling town in Pennsylvania, May made much of the eponymy. It gave her license to construe her own life story as myth, legend, and fairy tale. She had the uncanny ability to tell and sell stories with herself as the central character. Her stage roles—as a modern-day Cinderella, as possessor of a magic gem, as discovered starlet, as rags-to-riches heroine, as lady slave working to support her down-and-out household—all crossed over into her real life. Her character themes—possessing miraculous power, pursuing true love, fighting injustice, weathering curses, and finding redemption—captured the spirit of her times, and also the imagination of friends, fans, the press, and the general public.

Besides being a good tale of a fascinating and overlooked historical figure, Madcap May provides a cultural study of how an exceptional “new woman” emerged from a communal religious sect and how a small-town girl made the world her global stage during the formative period of modern American and British society. It demonstrates how a woman possessed of an indomitable spirit took control of her life and fought against entrenched institutions founded upon class, gender, and social and occupational privilege—and did so with incredible panache.

As a cultural anthropologist, I never imagined I would write such an account, but having conducted preliminary research about May a few years ago for my book Hope Diamond: The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem, I was struck by the sheer improbability of her larger-than-life story. Overcome with a sense of admiration for her fortitude and perseverance, I just had to write this book.

Richard Kurin

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C.

I just wanted to be different.1

– May Yohe

CHAPTER ONE

Bethlehem’s Daughter

MAY YOHE ALMOST ALWAYS LIED. She was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 1866 but often said it was 1869. She claimed she was a “true American,” but “no Yankee.”2 May proudly boasted, more than once, that her mother was an American Indian, specifically a “blue blooded” member of the “brave” Narragansett tribe.3 That fact, May said with absolutely no modesty, “sort of connects one with the creation of the world.”4 These claims typify May’s habit of myth-making and overstatement, for there is no evidence that she was descended from American Indians or that she ever acted upon any Native American beliefs.

At other times, May claimed to be a distant descendant of William Penn, founder of the Pennsylvania colony. When it suited her or her audience, she asserted a Parisian birth. May pronounced her last name “Yo-ey”—“without any accent anywhere,”5 she’d tell reporters, simultaneously acknowledging and obfuscating her Germanic ancestry. Indeed, when she said she was Pennsylvania Dutch, newspapers erroneously reported that her father was from Holland. May smiled and winked at that.

May was born to William and Elizabeth Yohe in Bethlehem’s Eagle Hotel. The hotel was owned by her grandparents, Caleb and Mary Yohe, though May sometimes referred to Caleb as her uncle. May spent her early years in Bethlehem, and the community had an enormous influence on her.

Bethlehem, about sixty miles north of Philadelphia, was founded in 1741 by a small band of Moravian settlers who had migrated from Georgia in a quest to convert Indians to Christianity. Moravians were industrious, ingenious, and community minded. They esteemed education highly, kept music at the center of their lives, and accorded women a high degree of independence and respect—values that would help shape May’s character. As May wrote, “I was brought up very strictly in the austere faith of the Moravian Church.”6 Though she may have been more mischievous than austere, and while she may not have been steeped in Moravian theological notions, May picked up many of the community’s values, particularly with regard to a girl’s horizons.

The Moravians were an early reformist sect that predated Martin Luther. Founded in the mid-fifteenth century, they were inspired by John Hus (1369–1415), an early Church reformer who was burned at the stake as a heretic. The sect was centered in Bohemia and Moravia, in what is now the Czech Republic. Persecuted in their homeland in the 1500s and 1600s, they reinvigorated their faith by developing a strong missionary purpose in the 1700s under the leadership of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf (1700–1760), a Lutheran Saxon, on whose estate they settled. After originating in central Europe, the Moravians spawned communities in Denmark, Ireland, England, the West Indies, North America, and even East Africa.

Count Zinzendorf visited Pennsylvania and gave Bethlehem its name on Christmas Eve 1741. The settlement would in ensuing years become the American capital for the Moravians, attracting a diversity of followers not only from Europe’s Germanic region but from countries such as Great Britain and Denmark. Moravian missionaries also brought former African-American slaves and Native Americans into their fold. Other Moravian settlements included Nazareth and Lititz in Pennsylvania and several towns near Salem in North Carolina, a region known as Wachovia and named after Zinzendorf’s ancestral lands.

The German-speaking Moravian settlers in Bethlehem quickly exploited the ample surrounding forests and wildlife, cleared farmland, and established cottage industries on the Monocacy Creek of the Lehigh River. They used water wheels to power a mill, an iron foundry, a pottery workshop, a tannery, and a system for pumping water uphill to their village through wooden pipes—an invention that impressed such visitors as Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

Guided by Zinzendorf’s philosophy and funding, the Moravians practiced a form of communalism called the “General Economy.” For the first generation, until Zinzendorf’s death in 1760, the Moravians were organized into “choirs.” These were groups of people of a common age and gender who lived together in a common house, sharing work and joining in worship. There were choir houses for boys, girls, married men, married women, and widows. In the early days of Bethlehem, it was the choir, rather than the nuclear family, that animated local society.

Education mattered deeply to Moravians, who saw it as a path to salvation. An early Moravian bishop, John Amos Comenius (1592–1670), a widely respected and influential Czech educator who had once been considered for the presidency of Harvard, was a strong advocate of universal education—a much more contentious proposition then than it is today. In Comenius’ view, science, rationality, and innovation were means of using God-given abilities to flourish as a human being. He believed in educating not only white men from privileged backgrounds, the norm at that time, but women and men in every social stratum and from every race and condition.

Though he never visited America, Comenius’s views strongly shaped the American Moravian community, where literacy approached one hundred percent and where schools were established for women, for African Americans, and for learning American Indian languages.

Music was also central to Moravian life. Music and singing were regarded as part of the liturgy, a vehicle for communing with the divine. Moravian choirs sang sacred songs in church, serenaded the sick and elderly, and entertained the community. All Moravians were also expected to be proficient on at least one instrument—often the piano, organ, violin, or trombone.

The community’s orientation toward women was especially significant to Moravians, their neighbors, and eventually May Yohe. In early Bethlehem’s General Economy, people of opposite sexes lived in segregated quarters. Women’s roles were clearly defined and encoded in dress, as indicated in the mid-eighteenth century paintings of John Valentine Haidt (1700–1780).7 Haidt’s portraits of women in the community depict them modestly, with long dresses and nary a hair protruding from their schneppelhaube, white linen head caps. Colored ribbons indicated their sexual status. Young girls tied their caps with red neck ribbons, eligible maidens with pink ones, wives with blue, and widows with white.

Despite such conventional representations, Moravian women, even in the eighteenth century, enjoyed a greater degree of equality with men than most of their contemporaries. Although boys and girls attended separate schools or classes, Bethlehem was noted for its girls’ schools, most notably the Female Seminary, known as the “Fem Sem.”

Both men and women were encouraged to pursue an advanced education. Women could own land and businesses, go to college, be ordained to direct communal religious rites, and lead the beloved choirs in song and prayer.

The special role of women among Moravians is related to their theological beliefs about the Christian Trinity. In American colonial times, these beliefs led to civic confrontation and even physical conflict with Protestants of other denominations. Moravian theology suggests that the Holy Spirit is female and that Jesus has a divine feminine aspect. Bethlehem’s early folk art echoed these ideas, depicting the crucified Jesus’ bleeding s

ide-wound as a life-giving, vagina-like spiritual womb.

Moravian women could thus identify personally and intimately with Jesus and the Holy Spirit and, by calling upon their divinity, be secure in their roles as preachers, leaders, and teachers. Moravians’ spiritual elevation of women challenged the more patriarchal orientation of other Protestant sects in the region, such as Lutherans, Methodists, and Dutch Reformed, who regarded some of the Moravian teachings as blasphemous.

Similarly, the Moravians were not shy about teaching their children about sex and depicting sex organs. Moravians strongly approved of legitimate sexual relations between a husband and wife, not only for the purposes of procreation, but in their own right as a God-given pleasure. Sex was not shameful or devilish, or associated with one’s lower nature, but worthy of celebration.

Young Moravian Girl, c. 1755–60. (photo credit 1.1)

The communal treatment of sexuality was unavoidable in the married choir house. There, men and women lived segregated by gender. With the full awareness of other house occupants, married couples scheduled and coordinated when they would copulate in the “marital chamber.” As other communities became aware of these Moravian practices and beliefs, they characterized them as shameful, promiscuous, and sinful.

By the 1760s, Bethlehem’s Moravians began to change some of these ideas and practices. They abandoned the mandatory General Economy, and the community’s several hundred members started living as families in nucleated households with private property. Some of the communal choirs continued on a voluntary basis.

Bethlehem’s industry served it well during the American Revolutionary War. Its workshops made guns for Washington’s army, even though its inhabitants did not fight—not because of pacifism, but rather out of respect to England for recognizing the Moravian Church. Bethlehem hosted what was then a state-of-the-art hospital whose physicians and nurses treated American war wounded, including the Marquis de Lafayette. During the war, the town’s premier hotel, the Sun Inn, hosted a “who’s who” of the time.

Madcap May

Madcap May